by D. Leilehua Yuen

With the Chinese pirate Shek Yang (Zheng Yi Sao) going viral after books and movies included her, I thought it would be fun to do some recipes of her homeland. She probably was born in the Xinhui area, on the Tanjian River. Using modern transportation, her homeland is about an hour drive from Zhongshan, the homeland of my own Chinese ancestors.

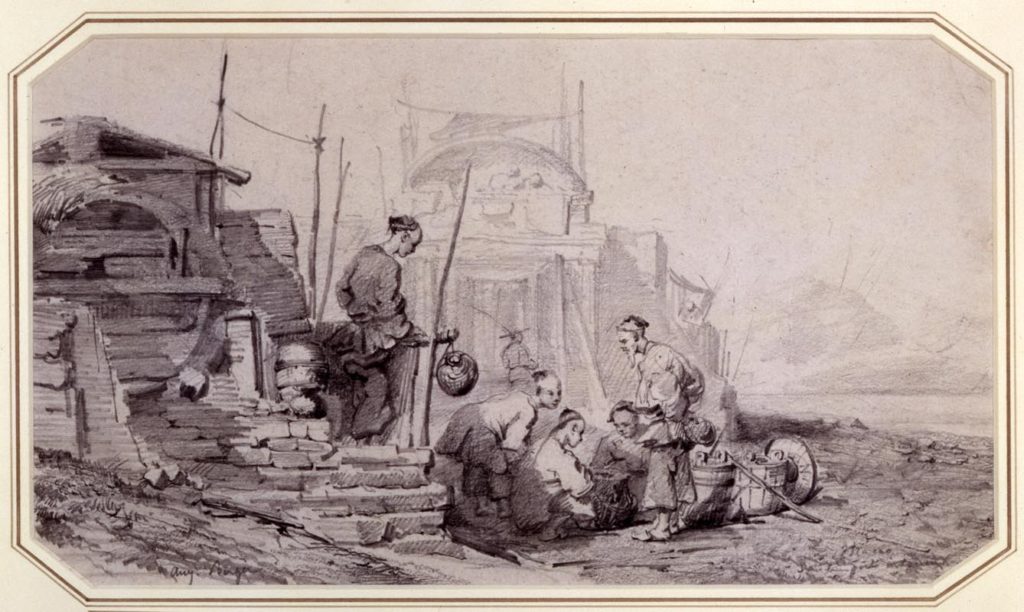

“The stern of the boat held a basic kitchen, with a tiny brick stove and some wood and kindling. We had an iron pot for making the simplest “fish rice,” as well as an iron plate for frying fish and shrimp. . .

“The boat was only five or six meters long. My father and grandfather would take turns standing at the bow to pole the boat forward and cast nets. The middle of the boat was a “ship’s cabin” made from a bamboo canopy, with long wooden boards fixed along either side. These served as both benches and beds. Clothing and food were stored beneath the boards on one side, while fishing nets were piled on the other side, along with water tanks, miscellaneous fishing gear, and repair tools. Whenever the sun was out, the top of the canopy would be covered with all kinds of drying fish.

“My mother made cloth curtains for the two sides of the cabin, so that we could change and groom ourselves with more privacy and keep out some of the wind and rain. “

Ah Jin, interview with Nathanial J. Gan Gone Ashore: Inside the Vanishing World of China’s “Sea Nomads”

Because of the challenges of cooking onboard a boat, meals probably were very simple, using as little fuel, space, and working time as possible. It seems that different styles of jook and other soups were the mainstay. Once in the pot, they can be left to simmer over a bed of coals. Dishes that required more complicated cooking, such as baking and frying in oil, might be purchased from nearby communities, though the Tanka were not welcomed in the towns.

At the bottom of this article I have a jook recipe, and found a couple of nice videos to share. I’ll add more recipes as I find them, so please check back!

Shek Yang probably was a descendant of the Baiyue, ethnic groups who inhabited the region for about 2,000 years before their tribes were assimilated into the expanding Han empire. The Book of Han describes various Yue tribes and says the peoples can be found from the regions of Kuaiji to Jiaozhi. They were described as having short hair, body tattoos, fine swords, and great naval prowess.

According to official Liu Zongyuan (Liou Tsung-yüan; 柳宗元; 773–819) of the Tang Dynasty, there were Tanka people settled in what are now Guangdong province and the Guangxi Zhang autonomous region.

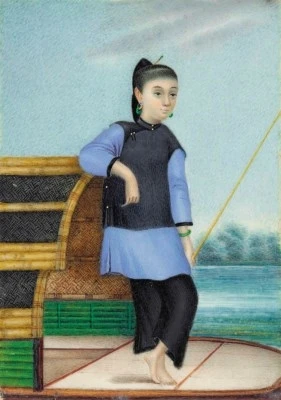

Chinese School of Art, 19th Century

Shek Yang probably dressed much like this young woman.

By the time of Shek Yang, the late 18th century through early 19th century, many of the Yue descendants had been pushed to the rivers and oceans, displaced by the Han communities in Guangdong who called the earlier inhabitants “Tanka” or “boat people.” The term is now considered derogatory and many discourage its use. Nàamhóiyàn (People of the Southern Sea) or Séuiseuhngyàn (People Born on the Waters) are gaining in usage.

The People Born on the Waters did not practice foot binding, they spoke their own dialect, and had their own style of music. They were forbidden to marry the land-dwelling Han Chinese, or even to live on land, except for some small houses at the water edge.

Today, the People Born on the Waters are facing changes from the environment, development, and society. I hope that they can navigate these new currents to live as they wish.

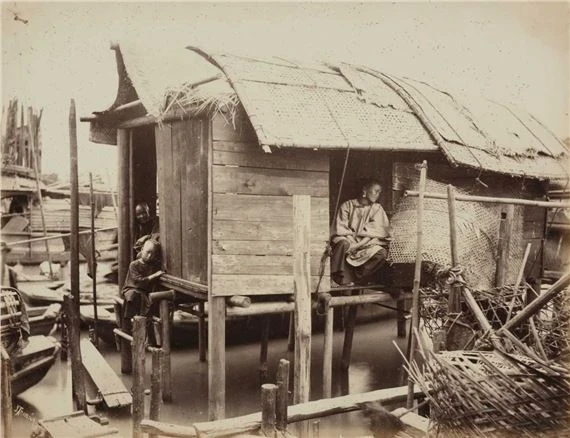

John Thomson, 1869

Shek Yang might have been born in a home similar to these. Land-based homes often were made from boats which had been pulled up out of the water, or the homes were constructed to be similar to a boat.

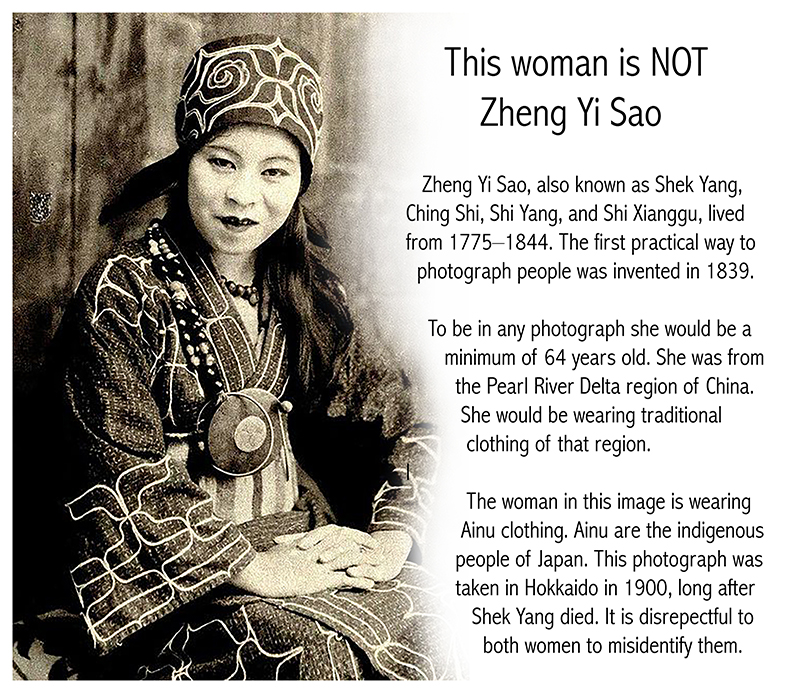

Unfortunately, many people are sharing turn-of-the-century photographs claiming that they are Shek Yang, and these images have nothing to do with her!

Though they should not be conflated, there are similarities between the Ainu and the Séuiseuhngyàn. Both are indigenous peoples, both were colonized and displaced, both are being severely impacted by environmental destruction.

You can learn about the Ainu people in this excellent documentary below by Dr. Kinko Ito, a professor of sociology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) in the United States. She conducted her research and many unstructured interviews in Hokkaido in 2011, 2012, and 2014. This ethnographic film features several Ainu people, and the interview topics include identity, marriage and family, human relations with non-Ainu Japanese, their history, and school and work experiences.

This image below also is not of Shek Yang. But the actress Crystal Yu is, indeed, lovely!

Shek Yang would have looked much more like this woman, below. Maybe I should make my own Shek Yang fan art?!

You can help support my research in global food and culture by becoming a patron of the Questing Feast Patreon page which continues to support the work and legacy of Geraldine Duncann.

Tingzai Zhou 艇仔粥 (Sampan Jook)

Tingzai Zhou is the modern spelling of the old-fashioned sampan jook I grew up with. This variety is also known as boater’s jook, boat congee, or any of several other names. Considered to have been developed by the Nàamhóiyàn of Lìzhī Wān (Lychee Bay) it’s a great one-pot meal. One pot meals that are easy to prepare, filling, and nutritious are important in the limited space of a boat! While my family is descended from the later Han inhabitants of the Zhongshan area, sampan jook became a popular dish throughout the Pearl River Delta.

Here is how my family prepares it:

If you don’t have an item, donʻt worry about it, just substitute something else that would taste good in the blend. This kind of cooking is not about following a specific recipe, but about adapting a basic recipe to what is available.

- Rice (white or brown short grain)

- Chicken carcass or pork bones

- Chicken meat

- Pork meat

- Shrimp

- Fish (I prefer a white flesh fish for this)

- Water chestnut, slivered

- Ginger, slivered

- Scallion, shredded

- Pi dan (hundred year egg), roughly chopped

- Fried peanuts

- Cook rice as you normally would. You will want about a half-cup of uncooked rice per person, plus one full cup. When we know we want to make jook, like when a storm is coming, we make lots of extra rice the night before.

- For the main proteins, combined, you will want about a half-cup per person.

- While the rice is cooking, or even the morning or night before, boil the chicken carcass and/or pork bones to create a broth. You want about 2 cups of broth per person. Strain all bones out of the broth.

- When the rice is cooked, add it to the broth and cook just below a simmer. Long slow cooking to make a porridge about the consistency of split pea soup. These days, I do this in my slow cooker.

- While the rice is cooking, prepare your other ingredients. I cut the pork, chicken, and fish into pieces about 1/2in by 1in or 2in. These are blanched to set and firm them. The fish, especially, will tend to fall apart in the jook if not set first. It will still be tasty, but there won’t be delicious chunks of fish to eat! Set them aside.

- If the shrimp is small enough to pick up with chopsticks and eat conveniently, just shell, de-vein, and blanch them. If it is too big, then after cleaning, cut them into bite-sized pieces.

- When the proteins are cooked, garnish the top with the remaining ingredients.

You can serve this in one big bowl with the garnishes already added, and people can scoop out what they want, or you can serve in individual bowls and people can add the garnishes they like.

Here is another way of preparing this hearty jook:

Youtiao 油條

Also known as yau char kway in Southern China and guǒzi in Northern China. It also has a multitude of other names throughout the dough-frying world!

For myself, I just buy them, so my advice on how to make them will not be the best. I guess I need to make them, though, as these days I cannot find anyone who sells them. I like this video series:

Resources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tanka_people

- https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1947244/uncertain-origins-hong-kongs-tanka-people

- https://www.thatsmags.com/china/post/23313/boat-people-south-china-s-tanka-adrift-on-uncertain-tides

- Smuggling networks

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-4079-7_5

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479721018764

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320451736_Food_Community_and_Ritual_in_the_Pearl_River_Delta-Revisiting_the_’Common_Pot’

- Gone Ashore: Inside the vanishing world of China’s “Sea Nomads”

- Photos: China’s Tanka people split between life at sea or on land

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=3729031907181150