It’s early Modern English. Like my mother, it annoys me when people add a “thee” or a “thou” and think they are speaking Old English. Nope. Not.

The Old English period (450-1100s) is followed by Middle English (1150–1500), Early Modern English (1500–1650) and finally Modern English (after 1650), and in Scotland Early Scots (before 1450), Middle Scots (c. 1450–1700) and Modern Scots (after 1700).

Now, of course, there is no specific year in which everyone got together and said, “Hey! It’s 1183, let’s stop sounding like Barbarians and switch to Middle English!”

There was evolution, overlap, and pockets of older speech remained in isolated areas. Some of those pockets died out, some caught up with the dominant language, and some evolved into their own separate languages.

We do have examples of text which have been carried across the years to us, and have preserved the changes. one familiar example is The Lord’s Prayer.

There are many versions of The Lord’s Prayer in each era, but these will give an idea of the changes the English language has seen in the past 2000 years.

The Lord’s Prayer in Old English

Fæder ure

þu þe eart on heofonum,

si þin nama gehalgod.

Tobecume þin rice.

Gewurþe ðin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofonum.

Urne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us todæg.

And forgyf us ure gyltas swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendum.

And ne gelæd þu us on costnunge,

ac alys us of yfele. Soþlice.

The Lord’s Prayer in Middle English

Oure fadir that art in heuenes,

halewid be thi name ;

thi kyngdoom come to ;

by thi wille don in erthe as in heuene :

Ʒyue to vs this dai oure breed ouer othir substaunce ;

and forƷyue to vs oure dettis,

as we forƷyuen to oure dettouris ;

and lede vs not in to temptacioun,

but delyuere vs fro yuel.

Amen

The Lord’s Prayer in Early Modern English (the version I grew up with)

Our father which art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done,

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive our trespassors.

Lead us not into temptation.

But deliver us from evil.

The Lord’s Prayer in Present-Day English

Our Father in heaven, may your name be honored,

May your kingdom come,

May your will be done

On earth as it is in heaven.

Give us our sustenance for today,

And forgive us our wrongs,

as we ourselves have forgiven our wrongdoers.

And do not lead us into doing wrong,

But deliver us from that which would lead us into wrong.

Now, if you, like me, want to give a FLAVOR of “Olden Tymes” to your speech, for cosplay, Renfaire, SCA, or what have you, then have fun with “speaking forsoothly!” Such speech be not of ein specific era, but rather an amalgamation drawn from thine own well of archaic speechcraft and presented from the mouth of thine character!

What does Old English sound like? Listen to this!

See the whole poem in Old English and Modern English by clicking this link.

Many Old English foods are still prepared today. If you enjoy meatballs or rissoles, you are carrying on the tradition. In a time when meat tended to be quite “toothy,” due to most of it being free range or game, mincing it up fine to cook made it more tender, juicy, and allowed an assortment of vegetables and various scrapings from previous meals to be incorporated. Here is a basic method for rissole.

Rissole

- meat

- parsley

- onion

- garlic

- vegetables

- eggs

- milk

- breadcrumbs

- gravy

Mince everything fine and blend all except the gravy, one egg, milk, and breadcrumbs together well. Of course, if you have LOTS of breadcrumbs, you can use some to stretch the meat mix. Make balls of the mix and then flatten them a bit. Mix together one of the eggs with some milk. Soak the flattened meatballs in the mix, then remove and roll in the breadcrumbs. Fry in hot oil until browned. If you will serve them dry with the gravy over, then continue to cook through. If they will be simmered in the gravy, do so as soon as they are browned so that they finish cooking in the gravy, lest they overcook and toughen.

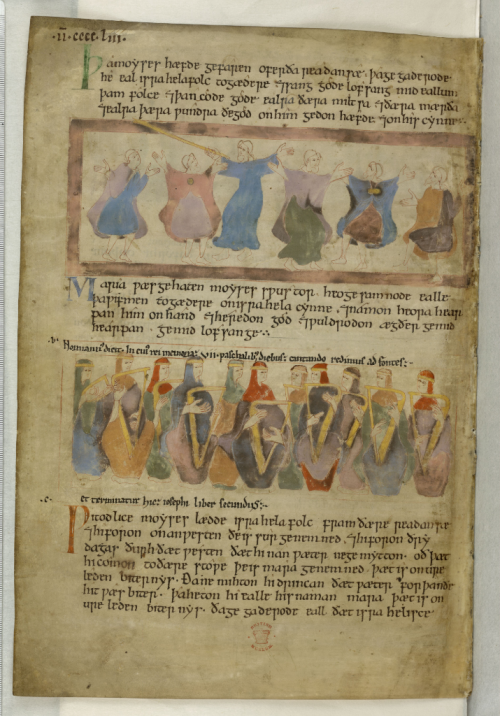

Be that as it may, here is a lovely page from the British Museum on how to create a medieval English feast.

Do you like our header image? Learn more about the Web Gallery of Art at this link.